Examples of Preventative Projects for Family of Depressed Patient

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care?

International Journal of Mental Wellness Systems volume xiv, Article number:23 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Similar to other health intendance sectors, mental health has moved towards the secondary prevention, with the endeavour to detect and care for mental disorders as early as possible. All the same, converging evidence sheds new lite on the potential of primary preventive and promotion strategies for mental health of young people. Nosotros aimed to reappraise such evidence.

Methods

We reviewed the current state of noesis on delivering promotion and preventive interventions addressing youth mental wellness.

Results

One-half of all mental disorders offset by fourteen years and are usually preceded by non-specific psychosocial disturbances potentially evolving in any major mental disorder and accounting for 45% of the global burden of disease across the 0–25 age bridge. While some activity has been taken to promote the implementation of services dedicated to young people, mental health needs during this critical period are still largely unmet. This urges redesigning preventive strategies in a youth-focused multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic framework which might early modify possible psychopathological trajectories.

Conclusions

Evidence suggests that it would exist unrealistic to consider promotion and prevention in mental wellness responsibleness of mental health professionals alone. Integrated and multidisciplinary services are needed to increase the range of possible interventions and limit the take chances of poor long-term effect, with besides potential benefits in terms of healthcare system costs. However, mental health professionals have the scientific, ethical, and moral responsibleness to indicate the direction to all social, political, and other health care bodies involved in the process of meeting mental health needs during youth years.

Background

Promotion, prevention and early intervention strategies may produce the greatest impact on people's health and well-beingness [1]. Screening strategies and early detection interventions may allow for more constructive healthcare pathways, by taking activity long before health problems worsen or by preventing their onset [2]. They as well permit for a more personalized care in terms of tailoring health interventions to the specific sociodemographic and health-related risk factors as well as activating interventions specific to affliction stage [3]. In this regard, the application of clinical staging models has been suggested to better wellness benefits, past addressing the needs of people presenting at unlike stages along the continuum between wellness and illness [4]. Despite challenging, reformulating health services in this perspective may increase prevention and early on intervention effectiveness, illness control and overall care, positively impacting on the wellness and well-existence outcomes of a broader population [five]. Not to exist overlooked, it may potentially reduce affliction burden and healthcare system costs [vi].

The need for implementing prevention and early intervention in youth mental health

Prevention and early intervention are recognized fundamental elements for minimizing the impact of whatever potentially serious health status. However, while representing a field of remarkable achievement, that of early on intervention in youth health is a target non completely accomplished even so [7]. This is particularly true for youth mental health. In fact, mental healthcare has been traditionally oriented to provide health benefits to developed populations during crisis events and major emergencies [8]. In this framework, mental health presentations to emergency settings in pediatric populations are somewhat frequent events [9]. Deinstitutionalization policies have only partially addressed this issue, also in light of the large variability worldwide in the implementation of community mental health services [10], especially for children and young adults [11].

Theoretical considerations about the opportunity to intervene in this specific age window in terms of mental health follow a number of evidence-based considerations. First, mental health is a fundamental component of the person's ability to function well in their personal and social life besides equally adopt strategies to cope with life events [12]. In this regard, early on babyhood years are highly of import, in light of the greater sensitivity and vulnerability of early on brain evolution, which may have long-lasting effects on academic, social, emotional, and behavioral achievements in adulthood [thirteen]. Second, near mental disorders accept their tiptop of incidence during the transition from childhood to young machismo, with up to 1 in 5 people experiencing clinically relevant mental health issues before the age of 25, 50% of whom being already symptomatic by the age of 14 [14]. Among people younger than 25 years old, mental health problems, especially anxiety and mood disorders, are the main cause of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), accounting for 45% of the global burden of disease, with problematic substance utilise including alcohol and illicit drugs being the chief risk factor for incident DALY (9%) [xv]. Third, nearly mental wellness services, as traditionally developed, have proven to be ineffective to provide healthcare during this disquisitional menses [16], with a modest employ of mental health services despite the high prevalence of mental wellness bug amongst immature individuals [17]. Too, following symptom onset, people aged 0–25 experience the greatest filibuster to initial treatment [eighteen]. This is mainly due to ii reasons. On one hand, young individuals, especially male, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and of indigenous minority, are less likely to found initial contact with mental health services and stigma represents a major barrier in this regards [19]. When they practise, they prove high rates of detachment [20]. On the other, significant delays in receiving care are besides attributable to the reduced power of services to speedily deliver specialist mental healthcare for youth in need afterward a first principal care consultation [21]. When treatments are finally offered, the majority are not evidence-based [16].

Based on prove summarized above, in that location is a pressing need to develop, or improve where nowadays, youth mental healthcare models which can implement prevention and early intervention strategies. While progress has been fabricated for psychotic disorders, likewise due to the successful application of an at-gamble mental state concept [22], this is still largely unexplored in the context of common mental disorders, such equally low, feet, substance abuse, and eating disorders [23]. In order to meet the need for early on intervention into childhood and immature machismo mental wellness difficulties, it is imperative to parallel redesign prevention and early intervention services for young populations, by promoting multidisciplinary collaborations betwixt different specialized professionals in an enhanced and integrated service of extended primary care [5].

The aim of this narrative review is threefold: (i) to update on the current debate on the at-risk mental state concept and the possibility of widening the clinical surface area of intervention beyond psychotic disorders; (ii) to review the part of psychosocial difficulties early on in life as potentially stable chance factors for poor mental health, and the extent to which they have been targets for early intervention; and (3) to report on the progress made then far in implementing collaborative and integrated services for youth mental health within the healthcare arrangement.

Methods

The current literature review is intended to bring together research evidence on early life risk factors detection, youth mental health service provision, and application of a clinical staging model by using a trans-diagnostic approach. In particular, the present work aims to emphasize the human relationship between these early on intervention components and offer new directions for clinical research into the full development of a youth-based model of mental healthcare focused on prevention.

Search strategy

A literature search was performed using electronic databases (MEDLINE, Web of Scientific discipline, and Scopus), using a combination of search terms describing run a risk factors, clinical staging, and multidisciplinary prevention and early interventions in youth mental wellness. Special attending was given to available research of the by 25 years every bit a major transition in the clinical label of the prodromal phase of major psychiatric disorders in youth has occurred during the by 2 to iii decades [21]. In addition, some research evidence gathered outside this search was reported, if considered appropriate by all authors.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in this review if assessing preventing strategies in youth in a trans-diagnostic and multidisciplinary arroyo. Studies were excluded in they (i) did not assess the awarding of a clinical staging model for youth mental health in a trans-diagnostic framework; (2) did not investigate youth mental health service provision in a multidisciplinary framework; (iii) primarily assessed gamble factors and preventive strategies in older populations rather than youth.

Towards a trans-diagnostic clinical staging model to intercept a wider at-hazard youth population

Over the nineteenth century, the and so-chosen "prodromal state" (i.e. the period preceding the onset of astringent mental disorders), was seen as a stage characterized past low-intensity or low-severity symptoms not sufficient to justify a categorical diagnosis, but whose ineluctable progression to full-blown disorder was just a matter of time. Towards the end of the last century, the formulation of the "at-gamble mental state" concept [22] has represented a milestone in the development of a preventive arroyo to mental disorders, by overcoming the stagnant thought of inevitably ominous prognosis. This has dramatically loosened the deterministic approach to more severe mental disorders, such every bit schizophrenia, in favor of a more cautious arroyo to the potential futurity evolution of the condition in a psychosis-spectrum context where milder forms of the disorder and recovery are even so possible. After a period of struggle to translate this paradigmatic advance in more effective mental healthcare practices, mostly because of the restrictive application of notions of "take chances" and "transition" on the basis of positive psychotic symptom manifestation lonely [24], we are finally facing a new turning point. Research evidence has increasingly recognized that, in addition to transition to psychosis, longer-term psychotic disorder, or persistent sub-threshold psychotic symptoms, progression to persistent mood, anxiety, personality and/or substance apply disorders is also a very mutual outcome [25, 26]. This adds to the contained bear witness that during development risk factors may contribute to a range of psychopathologies, and early indicators of later gamble are often dimensional [27]. For instance, babyhood adversities seem to impact negatively on a number of disorders [28]. Thus, in social club to amend narrate pluripotent and trans-diagnostic developmental processes and bio-behavioral mechanisms that give rise to mental illness, cross-disciplinary approaches need to integrate, if not overcome, the traditional diagnostic approach.

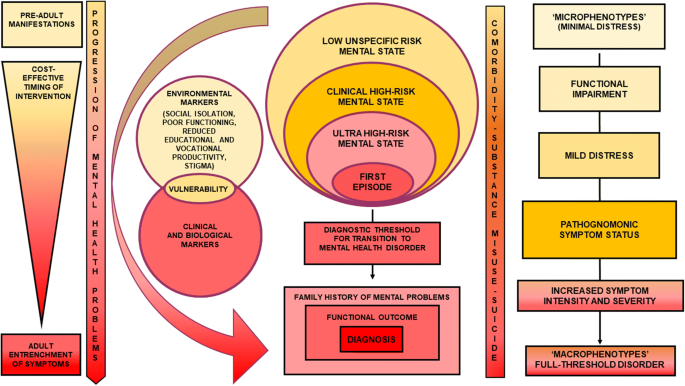

In this regards, integrated youth mental health services for people who are still in the before stages of a mental disorder may benefit from a wider clinical staging model framework far across the limited ultra-loftier take chances (UHR) prototype for psychosis. In particular, a trans-diagnostic clinical high-risk mental state (CHARMS) paradigm may increment chapters to intercept a wider range of lower risk cases than those with adulterate psychotic symptoms only, including people with sub-threshold bipolar and borderline personality symptoms likewise every bit balmy-moderate low [22] (Fig. 1).

A trans-diagnostic clinical staging model to intercept a wider clinical loftier-risk mental state population

Youth mental health: which targets for which interventions?

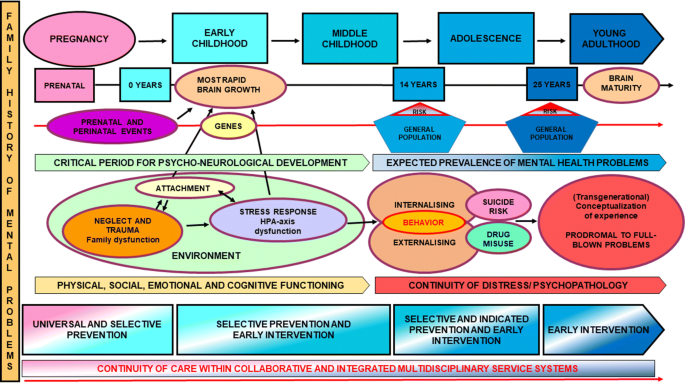

Neurodevelopmental changes occurring during youth brand information technology a catamenia of both vulnerability and opportunity for mental wellness. Research show indicates that a number of factors influence the person's mental health from before birth until early adulthood, later on which mental health can however be significantly modulated but to a bottom extent [29]. Meeting the child's physical (i.e. healthy nutrition), psychological (i.east. stable and responsive zipper relationships), and social (i.e. supportive and rubber environments) needs is key chemical element to support optimal encephalon development, emotional regulation, and higher order cerebral role, with long-lasting health benefits [thirty]. Conversely, adversities during pregnancy and early childhood such as inadequate care, neglect, and trauma, accept been shown to negatively impact on academic trajectories, psychosocial skills, physical resilience and the possibility of healthy aging [29, 31]. Also, depending on their nature, whether take chances or protective factors, such environmental determinants may differentially attune cistron expression and stress response, with enduring health effects [32]. For example, evidence from gene-surroundings interaction studies suggests that children carrying specific genetic variants are at increased risk for behavioral problems in later life, simply only when raised in dysfunctional families [33]. Similarly, regardless their severity, stressful life events produce the most 'toxic' effect on children'due south stress system, raising the risk of subsequent development of stress-related mental difficulties, when experienced in the absenteeism of a stable and supporting surround [34]. In this context, it appears particularly relevant the development of a secure attachment between the child and a protective chief caregiver, in social club to facilitate adaptive emotional and behavioral responses to stressful events [35]. In its absence, neurodevelopment may exist undermined, making that person more vulnerable to further environmental insults and subsequent development of both internalizing [36] and externalizing [37] behavioral problems, including anxiety, depression, substance misuse, maladaptive eating patterns, sexual run a risk behavior, and suicidality. The relation between attachment difficulties and youth psychological problems is nigh probable bidirectional, such that problematic behaviors during childhood and adolescence may also precipitate difficulties in the caregiver-child/adolescent attachment bond, or exacerbate preexisting dysfunctional patterns [38]. Research has shown that internalizing and externalizing disorders of childhood are associated with an increased likelihood to develop a psychiatric disorder later in adulthood [39]. Interestingly, stringent tests of homotypic (a disorder predicting itself overtime) and heterotypic (different disorders predicting ane another over time) prediction patterns suggest an increasingly developmentally and diagnostically nuanced picture, including but non limited to: (i) cross-prediction between anxiety and depression from adolescence to adulthood; (ii) adolescent oppositional defiant disorder, feet and substance disorders entirely accounting for the homotypic prediction pattern of depression overtime; and (iii) internalizing and externalizing psychopathology predicting psychosis-similar experiences and vice versa [40]. Overall, these findings highlight how single disorder-oriented trajectories offer limited prospects for preventive interventions. Instead, interventions addressing multiple co-occurring problems are more likely to impact positively on youth mental health, potentially interrupting the continuity between childhood internalizing and externalizing psychopathology that may besides co-occur with psychosis-like experiences on one manus, and psychiatric disorders in adulthood on the other. A large survey conducted by the World Health System (WHO) among 51,945 adults in 21 countries reported that eradication of childhood adversities, peculiarly those associated with maladaptive family functioning (e.g. parental mental illness, kid abuse, fail), would lead to a 29.8% reduction of any mental disorder lifetime, and an even higher reduction when considering exclusively adolescence- (32.3%) and babyhood-onset (38.2%) cases [28]. The possibility of preventing most i in 2 childhood-onset mental disorders is of crucial importance when considering that the feel of a mental disorder "kindles" a cascade of events which brand recurrence later in life more likely [41]. Thus, promoting selective preventive strategies supporting children's physiologic reactivity, cerebral control, and self-regulation through parenting- and classroom-based interventions, may correspond a massive preventive action and ensure the earliest possible access to intervention with a view of limiting the continuity of mental wellness problems from childhood through to adolescence and adulthood.

A summary of adventure factors and pluripotent pathological trajectory for mental disorders encompassing the youth prevention and early on intervention window is provided in Fig. ii.

Summary of take a chance factors and pluripotent pathological trajectory for mental disorders

Mental health prevention and early intervention in youth: where is the evidence?

Promotion of youth mental health

Mental health promotion focuses on enhancing the strengths, chapters and resource of individuals and communities to enable them to increase control over their mental health and its determinants. Prevention, on the other hand, aims to reduce the incidence, prevalence and severity of targeted mental health weather [42]. In society to fill the handling gap for mental, neurological, and substance apply disorders worldwide, evidence-based guidelines developed by the WHO recommend that population level health interventions had an overall promotion focus. This is in line with the well-established continuum of care between interventions promoting positive mental health, interventions striving to prevent the onset of mental health disorders (primary prevention), and interventions aiming at early identification, instance detection, early handling, and rehabilitation (secondary and third prevention) [43].

Meta-analytic work strongly supports the effectiveness of youth prevention programs addressing child abuse [44], negative consequences of parents' divorce on children [45], substance abuse [46], and school-related problematic behaviors [47] in reducing rates of psychosocial difficulties later in life [48]. In this regard, multimodal preventing programs combining preschool intervention and family support have been associated to the most indelible beneficial effects on a number of social outcomes, including meaning amend overall bookish performances and lower delinquency and antisocial beliefs rates [49]. However, it is worth mentioning that promotion practices endure from unlike mental health policies and social and contextual determinants. For instance, some wellness and social domains such as education, housing, nutrition, and healthcare, have pervasive influence on low income settings, while lack of supportive environments and community networks may accept more than detrimental furnishings in urban areas with loftier population density or ethnic minorities [50, 51]. Most likely, promotion programs crave tailoring to the specific socio-cultural setting. Depending on its critical issues and what interventions are needed most, the implementation of effective programs goes through reorienting health services. Besides, dialogue between health research, health professionals, health service institution, and governments is of paramount importance, peculiarly to evangelize integrated and multidisciplinary deportment for the benefit of the unabridged community [fifty].

Primary prevention in youth mental health

Developmental model for chief prevention

Principal prevention strategies may be universal, selective, or indicated, depending on whether they target the general population, a sub-grouping of the population, or specific individuals, respectively [42]. Rather than being separate, they should exist seen as an integrated set of preventive interventions that go on throughout the neurodevelopmental stages of life also as the intensification of risk [52].

Universal prevention (pre-clinical stage)

Mental health universal prevention aims at promoting normal neurodevelopment. Even though there is no consensus on which might exist the pathophysiological mechanisms to be addressed during early development, promising findings propose that developmental anomalies and behavioral deficits observed during childhood may be, at least partially, modifiable [53]. A number of effective pharmacological and psychosocial interventions for universal prevention have been identified, including: (i) perinatal phosphatidylcholine [54] and N-acetylcysteine [55] administration to support infants' encephalon development and anti-inflammatory neuroprotection; (ii) lifetime omega-3 fatty acrid [56,57,58], vitamin [57,58,59], sulforaphane [lx], and prebiotic [61] supplementation to support good mental health by reducing neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and microbiota dysbiosis; (iii) school-based behavioral interventions to minimize risk of bullying and peer rejection [62, 63] too as substance abuse [64, 65]; (iv) exercise training to support encephalon plasticity [66], structure [67] and connectivity [68] as well equally cerebral operation [69].

Selective prevention (clinical stage 0)

Selective interventions aim at preventing the manifestation of psychiatric symptoms, thus altering the developmental pathway to full-threshold disorders in the premorbid state. Recipients of these interventions are individuals whose chance of developing a mental disorder is significantly college than the rest of the population, while still beingness asymptomatic [42]. A number of take a chance factors accept been identified, including parental mental affliction [70], paternal age [71], maternal and obstetric complications of pregnancy [72, 73], flavour of birth [74], indigenous minority [75], immigration status [76], urban environment [77], infections [78], childhood adversities [28], vitamin D deficiency and malnutrition [79], low premorbid intelligence quotient [80], traumatic brain injury [81], and heavy tobacco [82] and cannabis employ [83, 84].

It is worth reporting that most risk factors are shared across multiple mental disorders, suggesting the poor validity of boundaries between diagnostic categories, at to the lowest degree at this stage [85]. Also, while some risk factors are hands correctible (due east.g. vitamin D deficiency) or technically preventable (due east.g. cannabis use, infections), other require restructuring the part of the youth mental wellness professional besides employing a core of paraprofessionals to piece of work more than intensively with a large population of at-risk immature individuals (east.one thousand. childhood adversities), and for withal others information technology is difficult to envisage programs ethically or practically sustainable (season of birth, urban environment) [86]. A few studies evaluated the effectiveness of prenatal and early infancy preventive programs for infants and children who may exist socially disadvantaged or potentially at risk [87, 88]. Results supported long-term positive effects of nursing domicile visits to expectant mothers and their families in hard social circumstances [87] also as schoolhouse educational interventions and home teaching to support depression-income families and their preschool children [88] in reducing kid abuse, neglect, and criminal behavior as well as improving the use of welfare and family socioeconomic status [87, 88].

To appointment, timing school-based mental health aid, assertiveness training, and stress and anxiety management have the greatest chance to prevent maladaptive beliefs and symptomatic manifestations [89]. Finally, while there is no clear research evidence favoring selective interventions in specific targeted populations, a promising strategy has been suggested to be the identification of those young individuals exposed to these risk factors who also have a family history of severe mental disease, in light of the per se higher genetic component for risk of mental disorders [90].

Indicated prevention (clinical phase ane)

Indicated interventions aim at the identification of those individuals at clinical loftier risk for the development of a mental disorder who are functionally impaired and no longer asymptomatic [42]. Psychosis studies have identified in the first 2 years post-obit the manifestation of functional impairment a menstruation of particular risk for transition to total-blown disorder [91], with about a third only in remission [92]. More recently, a shift towards a broader focus no longer confined to the psychosis risk identification has been suggested, in line with the increasingly clear show that pathways to mental disorders are pluripotent and trans-diagnostic [22]. This follows also the evidence that a so narrowed arroyo guarantees a limited detection, approximately 5%, fifty-fifty for those patients who will eventually develop a first episode of psychosis [93]. In this respect, complimentary evidence comes from a large meta-analysis that evaluated the impact of indicated preventive actions amid 4470 at-adventure students presenting with a range of bug including depression, anxiety, anger, general psychological distress, cognitive vulnerability, and interpersonal problems [94]. Intervention strategies included cerebral-behavioral, relaxation, social skills training, general behavior, social support, mindfulness, meditation, psychoeducational, acceptance and delivery therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, resilience training, and forgiveness programs. Results suggested that indicated interventions have positive effects not only in reducing the presenting problem simply besides in improving other areas of psychosocial adjustment [94].

Indicated interventions are nonetheless preventive and aim at altering the trajectory of mental disorders. Inquiry evidence suggests that the development of services for indicated prevention has met the objectives of strengthening service appointment, reducing the duration of untreated illness, and liaising with secondary prevention interventions [42]. In particular, reducing the duration of untreated disease has been robustly shown to impact positively on the result of first-episode psychosis and schizophrenia in many ways [95]. Increasing evidence suggests a similar effect for other psychiatric disorders including major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder [96]. Importantly, as some pre-diagnostic symptoms and neurobiological correlates are not specific for psychosis [97] and some undesired outcomes, such as decreased social functioning, quality of life, and occupational performance, are shared across mental disorders [98, 99], a hybrid strategy has been suggested in at-chance states involving symptom relief coupled to a reduction of transition [97]. In particular, command of symptoms and self-control of emotion and behavior every bit well as programs targeting poor social problem solving, low quality of social back up, interpersonal disharmonize, loneliness, and other social difficulties in at-adventure states may reduce the risk of progression to whatsoever mental health disorder, including bipolar disorder and depression [97].

Secondary prevention in youth mental health (clinical phase 2)

If patients progress to the manifestation of full-blown psychiatric symptoms, it is paramount to actively work towards securing early on and perchance complete recovery, past reaching a clinical and functional remission state. Secondary preventive strategies and early intervention services aim at mitigating the occurrence of negative prognostic factors such equally long duration of untreated disease, poor handling response, poor psychosocial well-existence and functioning, comorbid substance use, and high brunt on patients' families, with the last goal of preventing relapse or incomplete recovery [90]. In order to improve the effectiveness of early intervention in mental health, a Cochrane systematic review has confirmed the need for greater collaboration between main care sector and specialist mental healthcare services [100]. In this regard, 'consultation-liaison' and 'collaborative care' models seem to work better than the so-called 'replacement model', where main care physicians make unproblematic referrals to mental health services [100], for a number of youth-onset psychiatric disorders including depression [101,102,103,104], psychosis [105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117], bipolar disorder [118, 119], and panic disorder [120, 121], with promising bear witness for generalized feet disorder, social phobia [122], and somatoform disorders [123].

These multicomponent intervention programs involve the commitment of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, as well equally psychoeducation and skills training. However, disappointing bear witness from studies of the consequence of collaborative care on depression signal that the clinical improvement may not be maintained afterward discontinuing the multidisciplinary handling [101]. Thus, one may speculate that discharging immature people to principal care or generic mental health services, which are not designed to aid young populations in the early stages of a mental disorder, is likely to result in the erosion of the initial advantages of the collaborative care, thus non changing the trajectory and outcome of the condition. In the absenteeism of studies assessing the longer-term efficacy of such interventions, peculiarly in preventing poor outcome, treatment disengagement, and relapse, circumspection is being chosen [90].

Tertiary prevention in youth mental wellness (clinical stage iii)

Tertiary prevention represents the last opportunity to mitigate the bear on of mental wellness problems in youth. In fact, following the manifestation of a first episode of astute psychiatric symptoms, some patients may not reach full recovery, being still symptomatic or functionally impaired. Third preventive strategies aim at addressing treatment resistance, poor psychosocial wellbeing and performance, comorbid substance use, and loftier burden on patients' families, with the final goal of preventing multiple relapses and illness progression [90]. While the biological evidence for an association between multiple relapse and further deterioration is conflicting [124], inquiry suggests detrimental psychosocial and functional consequences of each relapse [125, 126]. The absenteeism of validated interventions to prevent multiple relapses highlights the limited protective effect of psychopharmacological treatments in the long-term, urging the development of new strategies to avoid chronicity (clinical stage 4).

A summary of promotion and preventive interventions in youth mental health is provided in Table 1.

Towards the evolution of integrated and multidisciplinary services for the young population

Over the last decade, reforming youth mental wellness services in the perspective of integration and collaboration between dissimilar healthcare professionals has gained increasing interest [127]. Parallel, early on intervention models, initially designed to assist people with psychotic disorders, have expanded their area of intervention to mood, personality, eating, and substance use disorders [128]. Thus, information technology has get increasingly possible to offer multidisciplinary and integrated healthcare to young people below the age of 25 with a diverseness of mental wellness difficulties besides as support their families.

In the Usa, the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project (MCPAP) promoted the creation of a statewide service favoring collaborations between primary intendance practices and specialized child and adolescent psychiatry services. MCPAP has a wide expanse of intervention including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, feet as well as initial psychopharmacological handling [129]. Studies accept shown that virtually primary intendance practices have enrolled in the program, increasing immature individuals' access to psychiatric services and overall satisfaction [130]. With the aim of productively integrating and enhancing collaborative care at all levels of prevention, the Massachusetts Mental Health Services Plan for Youth (MHSPY) has also implemented home-based integrated clinical interventions to assist severely impaired youth with mental, social, and substance use problems too equally their families in the community. Studies have shown benefits of MHSPY interventions in terms of higher psychosocial functioning and family satisfaction as well as lower burden on services and take chances to self and others [131].

In Australia, a 2006 government-funded initiative led to cosmos of 'Headspace', a multidisciplinary and integrated service offering early intervention for 12–25-year-one-time people with emerging mental health difficulties. Headspace has a broad area of intervention including mental health, physical health, vocational and educational support, and substance apply [132]. In a decade, cheers to the creation of 'communities of youth services' (CYSs), Headspace has seen growing the number of its centers from ten to more than 110, granting access to services to almost 100,000 young people per yr, including vulnerable, marginalized, and at-risk groups [eight]. An independent evaluation of Headspace has shown positive effects of the service in terms of reducing suicide ideation, self-harm, and number of absent schoolhouse or work days [133].

This healthcare model is transferred to other countries at an increasingly rapid rate. In Ireland, services called 'Headstrong' and 'Jigsaw' have developed, proving to be effective in facilitating access to community care to people anile 12–25 with emerging mental health difficulties [134]. In the Uk, a youth-based mental health service called 'Youth space' has implemented integrated health benefits for people aged 0–25 years in the Birmingham catchment area [135]. Similar models have been developed or under construction in Denmark, Israel, California, Canada (the Access, Adolescent/young adult Connections to Community-driven Early on Strengths-based and Stigma-free services), British Columbia ('The Foundry' model), and the netherlands (@ease) [eight]. Interestingly, research is following suit, with programs moving from the early identification of states immediately preceding psychosis onset in belatedly adolescence or early adulthood to the investigation of earlier phases of disease in vulnerable children and younger adolescents (east.g. London Child Health and Development Study) [136].

In summary, a mix of services is offered amid these models of care, in club to target mental wellness and beliefs, situational issues, concrete or sexual health, alcohol or other drugs apply, and vocational bug. Depending on the presenting business organization, the proportion of each delivered service can vary every bit well as the main service provider (general practitioner, psychologist, allied mental wellness etc.) and funding source [137]. Moreover, elements indicating best practice accept been identified, including being highly accessible (affordable, convenient, timely, non-stigmatizing, flexible, inclusive, and awareness raising), adequate (youth-friendly, confidential, respectful, engaging, responsive, competent, and collaborative), advisable (early on intervention focused, comprehensive, developmentally-appropriate, suitable to early stages of illness, suitable to complexity of presentation, testify-based, and quality assured), and sustainable (community-embedded, integrated inside a national network, finer managed, abet for young people'due south wellbeing). These elements correspond a framework to exist used to inform futurity development, performance indicators, and standards of care [138].

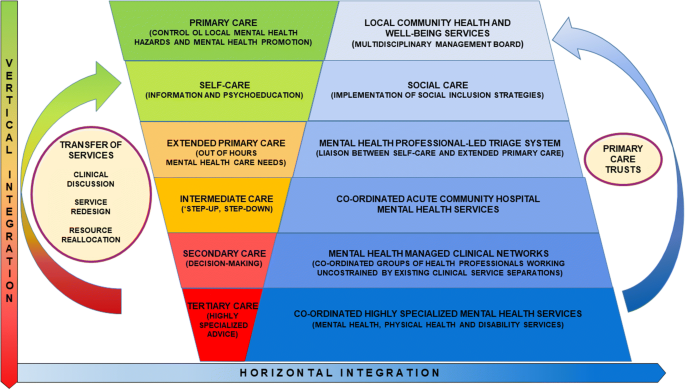

Even though the topic is non covered in this reappraisal, for the sake of abyss Fig. 3 shows the next steps that would be required to vertically and horizontally integrate this enhanced model of primary care with more specialized and intensive services as well as other components of the health and social organisation.

Vertical and horizontal integration of the enhanced model of master care for mental health

Conclusions and future directions

In social club to guarantee youth a healthy mental development through promotion, prevention, and early interventions, research testify supports the implementation of healthcare systems integrating mental, primary, and social care [128]. The contempo implementation of mental wellness services for the 0–25 age bridge [8] poses new questions nearly what is needed now for this model of care to fulfill its potential. The continuity of youth mental health needs from an early age seems to go across the boundaries of what falls within the mental wellness professionals' competences and duties, putting at stake the epistemological status of psychiatry. The mental health care sector has among its prerogatives the provision of effective interventions from early on stages of illness to long-lasting conditions. However, it is increasingly clear how crucial is to evangelize sustained early intervention across all potential stages, including the preclinical one, in order to avoid intermittent back up and not to lose initial progresses. So, what do mental health professionals have to do? Medicalize potentially serious problems at the preclinical phase? Potentiate the social management of at-chance conditions? Both? In the mental health field, attempts of reductio at unum have left much to be desired in all ages, highlighting the greater complexity of the question. The contempo debates about renaming mental health conditions or recognizing new ones on the footing of research bear witness, far from being a mere hermeneutic or linguistic upshot, underline the difficulty of managing what, through decades of clinical research, is emerging beneath the tip of the iceberg [139]. Promotion and prevention in mental health are not necessarily responsibility of mental wellness professionals alone. Inquiry evidence summarized in this review suggests that wellness researchers and professionals also as wellness service institutions and governments accept to join forces to deliver integrated and multidisciplinary actions in mental wellness, peculiarly in the early steps of the prevention chain. Mental health professionals accept anyway the scientific, ethical, and moral responsibleness to orient social, political, and overall health care actors involved in promotion and maintenance of mental health condition.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicative.

Abbreviations

- Access:

-

Adolescent/young developed Connections to Customs-driven Early Strengths-based and Stigma-free services

- CHARMS:

-

Clinical high-gamble mental state

- CYSs:

-

Communities of youth services'

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life-years

- MCPAP:

-

Massachusetts Kid Psychiatry Access Projection

- MHSPY:

-

Massachusetts Mental Wellness Services Program for Youth

- UHR:

-

Ultra-high risk

- USA:

-

Usa of America

- WHO:

-

Earth Health Organization

References

-

Parry TS. The effectiveness of early intervention: a disquisitional review. J Paediatr Child Wellness. 1992;28(5):343–vi.

-

Marmot G, Friel Due south, Bong R, Houweling TA, Taylor S, Health CoSDo. Closing the gap in a generation: wellness equity through action on the social determinants of wellness. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–9.

-

Schleidgen S, Klingler C, Bertram T, Rogowski WH, Marckmann One thousand. What is personalized medicine: sharpening a vague term based on a systematic literature review. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14:55.

-

Shah J, Scott J. Concepts and misconceptions regarding clinical staging models. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41(6):E83–four.

-

Allen D, Gillen E, Rixson L. The effectiveness of integrated care pathways for adults and children in health care settings: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2009;seven(three):80–129.

-

Stevens M. The costs and benefits of early interventions for vulnerable children and families to promote social and emotional wellbeing: economics conference. London: National Establish for Wellness and Intendance Excellence; 2011.

-

Shonkoff JP, Meisels SJ. Early childhood intervention: The evolution of a concept. In: Meisels SJ, Shonkoff JP, editors. Handbook of early on babyhood intervention. New York: Cambridge University Printing; 1990. p. 3–31.

-

McGorry PD, Mei C. Early on intervention in youth mental health: progress and future directions. Evid Based Ment Wellness. 2018;21(iv):182–four.

-

Hiscock H, Neely RJ, Lei Southward, Freed Thousand. Paediatric mental and physical health presentations to emergency departments, Victoria, 2008-xv. Med J Aust. 2018;208(8):343–8.

-

Thornicroft G, Deb T, Henderson C. Community mental health intendance worldwide: current status and further developments. Globe Psychiatry. 2016;15(iii):276–86.

-

Burns J, Birrell E. Enhancing early appointment with mental health services by young people. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2014;vii:303–12.

-

WHO. Mental wellness action plan 2013–2020. Geneva: Earth Health Organisation; 2013.

-

Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, Andersen CT, DiGirolamo AM, Lu C, et al. Early babyhood development coming of age: science through the life class. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):77–xc.

-

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and historic period-of-onset distributions of DSM-Four disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602.

-

Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, et al. Global burden of disease in young people anile ten–24 years: a systematic assay. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2093–102.

-

Andrews G, Sanderson G, Corry J, Lapsley HM. Using epidemiological data to model efficiency in reducing the burden of depression*. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2000;3(iv):175–86.

-

Costello EJ, Copeland W, Cowell A, Keeler G. Service costs of caring for adolescents with mental disease in a rural community, 1993–2000. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):36–42.

-

Catania LS, Hetrick SE, Newman LK, Purcell R. Prevention and early intervention for mental health problems in 0–25 year olds: are there evidence-based models of intendance? Adv Ment Health. 2011;10(1):6–nineteen.

-

Gronholm PC, Thornicroft Grand, Laurens KR, Evans-Lacko Due south. Mental health-related stigma and pathways to care for people at risk of psychotic disorders or experiencing starting time-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2017;47(eleven):1867–79.

-

Kim DJ, Brown E, Reynolds S, Geros H, Sizer H, Tindall R, et al. The rates and determinants of detachment and subsequent re-engagement in young people with start-episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54:945–53.

-

Fusar-Poli P. Integrated mental health services for the developmental period (0 to 25 Years): a critical review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry. 2019;ten:355.

-

McGorry PD, Mei C. Ultra-high-risk paradigm: lessons learnt and new directions. Evid Based Ment Wellness. 2018;21(iv):131–3.

-

Das JK, Salam RA, Lassi ZS, Khan MN, Mahmood W, Patel V, et al. Interventions for adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(4S):S49–60.

-

van Os J, Guloksuz S. A critique of the "ultra-high risk" and "transition" paradigm. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):200–6.

-

Lin A, Forest SJ, Nelson B, Beavan A, McGorry P, Yung AR. Outcomes of nontransitioned cases in a sample at ultra-loftier chance for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(3):249–58.

-

Rutigliano M, Valmaggia L, Landi P, Frascarelli M, Cappucciati M, Sear Five, et al. Persistence or recurrence of non-psychotic comorbid mental disorders associated with 6-year poor functional outcomes in patients at ultra high adventure for psychosis. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:101–ten.

-

Cuthbert B. The RDoC framework: facilitating transition from ICD/DSM to dimensional approaches that integrate neuroscience and psychopathology. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):28–35.

-

Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO Earth Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):378–85.

-

Mustard JF. Brain development, child development—adult health and well-being and paediatrics. Paediatr Child Health. 1999;iv(eight):519–20.

-

Maggi S, Irwin LJ, Siddiqi A, Hertzman C. The social determinants of early child development: an overview. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46(11):627–35.

-

Fonagy P, Target M. Attachment and reflective function: their office in self-organization. Dev Psychopathol. 1997;ix(4):679–700.

-

Fox SE, Levitt P, Nelson CA. How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain compages. Kid Dev. 2010;81(1):28–40.

-

Taylor A, Kim-Cohen J. Meta-assay of cistron-environs interactions in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;nineteen(4):1029–37.

-

Shonkoff JP. Building a new biodevelopmental framework to guide the future of early childhood policy. Child Dev. 2010;81(1):357–67.

-

Sroufe LA. Zipper and development: a prospective, longitudinal written report from birth to adulthood. Attach Hum Dev. 2005;7(4):349–67.

-

Groh AM, Roisman GI, van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Fearon RP. The significance of insecure and disorganized attachment for children'southward internalizing symptoms: a meta-analytic study. Child Dev. 2012;83(ii):591–610.

-

Fearon RP, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, Lapsley AM, Roisman GI. The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children's externalizing behavior: a meta-analytic study. Child Dev. 2010;81(ii):435–56.

-

Kobak R, Zajac K, Herres J, Krauthamer Ewing ES. Attachment based treatments for adolescents: the secure wheel as a framework for assessment, treatment and evaluation. Attach Hum Dev. 2015;17(2):220–39.

-

Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):764–72.

-

Lancefield KS, Raudino A, Downs JM, Laurens KR. Trajectories of childhood internalizing and externalizing psychopathology and psychotic-like experiences in adolescence: a prospective population-based accomplice study. Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28(2):527–36.

-

Rutter M, Kim-Cohen J, Maughan B. Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. J Kid Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(three–4):276–95.

-

WHO. Prevention of mental disorders. Effective interventions and policy options. Geneva: Earth Health Organisation; 2004.

-

Dua T, Barbui C, Clark N, Fleischmann A, Poznyak V, van Ommeren Yard, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Med. 2011;viii(11):e1001122.

-

Davis MK, Gidycz CA. Child sexual abuse prevention programs: a meta-analysis. J Clin Child Psychol. 2000;29(2):257–65.

-

Lee CM, Bax KA. Children's reactions to parental separation and divorce. Paediatr Kid Wellness. 2000;5(four):217–8.

-

Tobler NS. Meta-analysis of adolescent drug prevention programs: results of the 1993 meta-analysis. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;170:5–68.

-

Wilson D, Gottfredson D, Najaka S. Schoolhouse-based prevention of trouble behaviors: a meta-analysis. J Quant Criminol. 2001;17(iii):247–72.

-

Durlak JA, Wells AM. Principal prevention mental health programs for children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Am J Community Psychol. 1997;25(ii):115–52.

-

Yoshikawa H. Long term effects of early childhood programs on social outcomes and delinquency. Futurity Child. 1995;five(3):51–75.

-

Castillo EG, Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Shadravan S, Moore Eastward, Mensah MO, Docherty M, et al. Community interventions to promote mental health and social equity. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(5):35.

-

Jané-Llopis E, Barry M, Hosman C, Patel 5. Mental health promotion works: a review. Promot Educ. 2005; 12(Suppl 2):9–25, 61, 7.

-

Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A developmental psychopathology perspective on boyhood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;lxx(1):6–20.

-

Ghosh A, Michalon A, Lindemann L, Fontoura P, Santarelli Fifty. Drug discovery for autism spectrum disorder: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(ten):777–xc.

-

Ross RG, Hunter SK, McCarthy L, Beuler J, Hutchison AK, Wagner BD, et al. Perinatal choline effects on neonatal pathophysiology related to later schizophrenia risk. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(three):290–8.

-

Jenkins DD, Wiest DB, Mulvihill DM, Hlavacek AM, Majstoravich SJ, Chocolate-brown TR, et al. Fetal and neonatal furnishings of Northward-acetylcysteine when used for neuroprotection in maternal chorioamnionitis. J Pediatr. 2016;168(67–76):e6.

-

Pusceddu MM, Kelly P, Stanton C, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. North-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids through the Lifespan: Implication for Psychopathology. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;nineteen(12):pyw078.

-

Dawson SL, Bowe SJ, Crowe TC. A combination of omega-three fatty acids, folic acid and B-group vitamins is superior at lowering homocysteine than omega-3 alone: a meta-assay. Nutr Res. 2016;36(6):499–508.

-

Kurtys Eastward, Eisel ULM, Verkuyl JM, Broersen LM, Dierckx RAJO, de Vries EFJ. The combination of vitamins and omega-three fat acids has an enhanced anti-inflammatory effect on microglia. Neurochem Int. 2016;99:206–14.

-

Eryilmaz H, Dowling KF, Huntington FC, Rodriguez-Thompson A, Soare TW, Beard LM, et al. Clan of prenatal exposure to population-broad folic acrid fortification with contradistinct cognitive cortex maturation in youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):918–28.

-

Do KQ, Cuenod M, Hensch TK. Targeting oxidative stress and aberrant critical period plasticity in the developmental trajectory to schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):835–46.

-

Fond G, Boukouaci West, Chevalier G, Regnault A, Eberl Chiliad, Hamdani N, et al. The "psychomicrobiotic": targeting microbiota in major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2015;63(one):35–42.

-

Waasdorp TE, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ. The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(2):149–56.

-

Nocentini A, Menesini E. KiVa anti-bullying programme in italia: evidence of effectiveness in a randomized control trial. Prev Sci. 2016;17(eight):1012–23.

-

Patnode CD, O'Connor Eastward, Rowland Thou, Burda BU, Perdue LA, Whitlock EP. Primary care behavioral interventions to preclude or reduce illicit drug use and nonmedical pharmaceutical apply in children and adolescents: a systematic bear witness review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(nine):612–20.

-

Vogl LE, Newton NC, Champion KE, Teesson M. A universal harm-minimisation approach to preventing psychostimulant and cannabis utilise in adolescents: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2014;nine:24.

-

Cotman CW, Berchtold NC. Practice: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain wellness and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(six):295–301.

-

Draganski B, Gaser C, Busch Five, Schuierer Grand, Bogdahn U, May A. Neuroplasticity: changes in grey affair induced by training. Nature. 2004;427(6972):311–2.

-

Douw L, Nieboer D, van Dijk BW, Stam CJ, Twisk JW. A good for you encephalon in a healthy trunk: encephalon network correlates of physical and mental fettle. PLoS Ane. 2014;9(2):e88202.

-

Lee TM, Wong ML, Lau BW, Lee JC, Yau SY, And so KF. Aerobic exercise interacts with neurotrophic factors to predict cognitive operation in adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:214–24.

-

Rasic D, Hajek T, Alda M, Uher R. Risk of mental illness in offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of family high-gamble studies. Schizophr Balderdash. 2014;40(i):28–38.

-

Malaspina D, Gilman C, Kranz TM. Paternal age and mental health of offspring. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(6):1392–six.

-

Lukkari S, Hakko H, Herva A, Pouta A, Riala K, Räsänen P. Exposure to obstetric complications in relation to subsequent psychiatric disorders of adolescent inpatients: specific focus on gender differences. Psychopathology. 2012;45(5):317–26.

-

Cannon K, Jones PB, Murray RM. Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: historical and meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(7):1080–92.

-

Castrogiovanni P, Iapichino S, Pacchierotti C, Pieraccini F. Season of birth in psychiatry. A review. Neuropsychobiology. 1998;37(iv):175–81.

-

Bécares L, Dewey ME, Das-Munshi J. Ethnic density effects for developed mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Psychol Med. 2018;48(12):2054–72.

-

Hollander AC, Dal H, Lewis G, Magnusson C, Kirkbride JB, Dalman C. Refugee migration and risk of schizophrenia and other not-melancholia psychoses: cohort written report of 1.3 million people in Sweden. BMJ. 2016;352:i1030.

-

Vassos E, Agerbo East, Mors O, Pedersen CB. Urban-rural differences in incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in Kingdom of denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(5):435–40.

-

Sutterland AL, Fond Chiliad, Kuin A, Koeter MW, Lutter R, van Gool T, et al. Beyond the association. Toxoplasma gondii in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and habit: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(3):161–79.

-

Lerner PP, Sharony L, Miodownik C. Association between mental disorders, cognitive disturbances and vitamin D serum level: current state. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;23:89–102.

-

Stratta P, Riccardi I, Tomassini A, Marronaro K, Pacifico R, Rossi A. Premorbid intelligence of inpatients with different psychiatric diagnoses does not differ. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;four(vi):1241–4.

-

Andelic N, Sigurdardottir S, Schanke AK, Sandvik L, Sveen U, Roe C. Disability, concrete wellness and mental health 1 year after traumatic encephalon injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(13):1122–31.

-

Gurillo P, Jauhar Due south, Murray RM, MacCabe JH. Does tobacco use cause psychosis? Systematic review and meta-assay. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;two(8):718–25.

-

Monshouwer Thousand, Van Dorsselaer S, Verdurmen J, Bogt TT, De Graaf R, Vollebergh W. Cannabis use and mental health in secondary schoolhouse children. Findings from a Dutch survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:148–53.

-

Colizzi M, Murray R. Cannabis and psychosis: what do nosotros know and what should we do? Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(four):195–vi.

-

Uher R, Zwicker A. Etiology in psychiatry: embracing the reality of poly-gene-environmental causation of mental disease. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):121–nine.

-

Shastri PC. Promotion and prevention in child mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(two):88–95.

-

Olds D, Eckenrode J, Henderson C, Kitzman H, Powers J, Cole R, et al. Long-term furnishings of home visitation on maternal life course and child corruption and neglect—fifteen-year follow-upwardly of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997;278(8):637–43.

-

Schweinhart L. Long-term follow-upward of a preschool experiment. J Exp Criminol. 2013;nine(4):389–409.

-

Greenberg Thou, Weissberg R, O'Brien Thou, Zins J, Fredericks Fifty, Resnik H, et al. Enhancing schoolhouse-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. Am Psychol. 2003;58(6–vii):466–74.

-

Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, Kane JM. Improving outcomes of first-episode psychosis: an overview. Globe Psychiatry. 2017;xvi(three):251–65.

-

Kempton MJ, Bonoldi I, Valmaggia 50, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P. Speed of psychosis progression in people at ultra-high clinical take chances: a complementary meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):622–3.

-

Simon AE, Borgwardt S, Riecher-Rössler A, Velthorst E, de Haan Fifty, Fusar-Poli P. Moving beyond transition outcomes: meta-assay of remission rates in individuals at high clinical risk for psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(iii):266–72.

-

Fusar-Poli P, Rutigliano G, Stahl D, Davies C, Bonoldi I, Reilly T, et al. Development and validation of a clinically based risk computer for the transdiagnostic prediction of psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(v):493–500.

-

Conley CS, Shapiro JB, Kirsch AC, Durlak JA. A meta-analysis of indicated mental health prevention programs for at-risk college educational activity students. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64(two):121–forty.

-

Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland K, Lim S, Gifford G, McGuire P, et al. Tin can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Balderdash. 2018;44(half-dozen):1362–72.

-

Dell'Osso B, Glick I, Baldwin D, Altamura A. Can long-term outcomes be improved by shortening the elapsing of untreated illness in psychiatric disorders? A Conceptual Framework. Psychopathology. 2013;46(1):14–21.

-

Millan MJ, Andrieux A, Bartzokis Yard, Cadenhead K, Dazzan P, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Altering the course of schizophrenia: progress and perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(7):485–515.

-

Filho Equally, Hetem LA, Ferrari MC, Trzesniak C, Martín-Santos R, Borduqui T, et al. Social anxiety disorder: what are we losing with the current diagnostic criteria? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(3):216–26.

-

Goldney RD, Fisher LJ, Dal Grande East, Taylor AW. Subsyndromal low: prevalence, use of health services and quality of life in an Australian population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(iv):293–eight.

-

Bower P, Sibbald B. Systematic review of the upshot of on-site mental health professionals on the clinical behaviour of general practitioners. BMJ. 2000;320(7235):614–7.

-

Asarnow J, Jaycox L, Tang Fifty, Duan N, LaBorde A, Zeledon L, et al. Long-term benefits of short-term quality improvement interventions for depressed youths in main intendance. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1002–10.

-

Clarke G, Debar Fifty, Lynch F, Powell J, Gale J, O'Connor Eastward, et al. A Randomized effectiveness trial of brief cerebral-behavioral therapy for depressed adolescents receiving antidepressant medication. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(9):888–98.

-

Richardson L, Ludman East, McCauley East, Lindenbaum J, Larison C, Zhou C, et al. Collaborative care for adolescents with depression in chief care a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(eight):809–16.

-

Richards D, Colina J, Gask L, Lovell Thousand, Chew-Graham C, Bower P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of collaborative care for low in Great britain primary intendance (Buck): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f4913.

-

Craig T, Garety P, Power P, Rahaman N, Colbert S, Fornells-Ambrojo Chiliad, et al. The Lambeth Early on Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early on psychosis. BMJ. 2004;329(7474):1067–70.

-

Kuipers Eastward, Holloway F, Rabe-Hesketh S, Tennakoon L. An RCT of early intervention in psychosis: croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(five):358–63.

-

Grawe R, Falloon I, Widen J, Skogvoll East. Two years of continued early treatment for recent-onset schizophrenia: a randomised controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(5):328–36.

-

Sigrunarson V, Grawe R, Morken G. Integrated treatment vs handling-as-usual for recent onset schizophrenia; 12 year follow-up on a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;thirteen:200.

-

Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Ohlenschlaeger J, le Quach P, et al. V-year follow-upwards of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard handling for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. Curvation Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(seven):762–71.

-

Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, Abel M, Ohlenschlaeger J, Christensen T, et al. A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a get-go episode of psychotic illness. BMJ. 2005;331(7517):602–5.

-

Nishida A, Ando S, Yamasaki S, Koike S, Ichihashi K, Miyakoshi Y, et al. A randomized controlled trial of comprehensive early intervention care in patients with kickoff-episode psychosis in Nihon: 1.five-twelvemonth outcomes from the J-CAP written report. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;102:136–41.

-

Secher R, Hjorthoj C, Austin S, Thorup A, Jeppesen P, Mors O, et al. X-twelvemonth follow-upwardly of the OPUS specialized early intervention trial for patients with a offset episode of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):617–26.

-

Kane J, Robinson D, Schooler N, Mueser Grand, Penn D, Rosenheck R, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH Raise early on treatment programme. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362–72.

-

Ruggeri Thou, Bonetto C, Lasalvia A, Fioritti A, de Girolamo G, Santonastaso P, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of a multi-element psychosocial intervention for start-episode psychosis: results from the cluster-randomized controlled Get Upward PIANO trial in a catchment area of 10 million inhabitants. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(5):1192–203.

-

Srihari V, Tek C, Kucukgoncu Due south, Phutane Five, Breitborde N, Pollard J, et al. Showtime-episode services for psychotic disorders in the U.s.a. public sector: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(seven):705–12.

-

Chang W, Chan One thousand, Jim O, Lau Due east, Hui C, Chan S, et al. Optimal duration of an early intervention programme for first-episode psychosis: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(6):492–500.

-

Chang W, Kwong 5, Chan G, Jim O, Lau E, Hui C, et al. Prediction of functional remission in first-episode psychosis: 12-month follow-upwardly of the randomized-controlled trial on extended early intervention in Hong Kong. Schizophr Res. 2016;173(1–two):79–83.

-

Simon G, Ludman E, Bauer Grand, Unutzer J, Operskalski B. Long-term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care program for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):500–8.

-

Kilbourne A, Prenovost K, Liebrecht C, Eisenberg D, Kim H, Un H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a collaborative intendance intervention for mood disorders by a National Commercial Health Plan. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(iii):219–24.

-

Katon W, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, Cowley D. Cost-effectiveness and cost get-go of a collaborative care intervention for principal care patients with panic disorder. Curvation Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(12):1098–104.

-

Roy-Byrne P, Katon W, Cowley D, Russo J. A randomized effectiveness trial of collaborative care for patients with panic disorder in chief care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(ix):869–76.

-

Curth Northward, Brinck-Claussen U, Davidsen A, Lau Yard, Lundsteen Grand, Mikkelsen J, et al. Collaborative treat panic disorder, generalised feet disorder and social phobia in general practice: study protocol for three cluster-randomised, superiority trials. Trials. 2017;xviii:382.

-

van Dessel N, den Boeft M, van der Wouden J, Kleinstauber K, Leone Due south, Terluin B, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;xi:CD011142.

-

Jollans Fifty, Whelan R. Neuromarkers for mental disorders: harnessing population neuroscience. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:242.

-

Fikreyesus M, Soboka Yard, Feyissa M. Psychotic relapse and associated factors among patients attending health services in Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional written report. Bmc Psychiatry. 2016;16:354.

-

Gbiri C, Badru F, Ladapo H, Gbiri A. Socio–economic correlates of relapsed patients admitted in a Nigerian mental health institution. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;xv(1):nineteen–26.

-

McGorry P, Bates T, Birchwood G. Designing youth mental wellness services for the 21st century: examples from Australia, Ireland and the UK. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2013;54:s30–5.

-

Malla A, Iyer South, McGorry P, Cannon M, Coughlan H, Singh Due south, et al. From early intervention in psychosis to youth mental health reform: a review of the evolution and transformation of mental health services for immature people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(three):319–26.

-

Connor DF, McLaughlin TJ, Jeffers-Terry K, O'Brien WH, Stille CJ, Immature LM, et al. Targeted child psychiatric services: a new model of pediatric principal clinician–child psychiatry collaborative care. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45(5):423–34.

-

Straus JH, Sarvet B. Behavioral health care for children: the massachusetts child psychiatry access project. Wellness Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(12):2153–61.

-

Grimes KE, Mullin B. MHSPY: a children's health initiative for maintaining at-run a risk youth in the community. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006;33(2):196–212.

-

McGorry PD, Tanti C, Stokes R, Hickie IB, Carnell K, Littlefield LK, et al. headspace: Australia'due south National Youth Mental Health Foundation–where young minds come commencement. Med J Aust. 2007;187(7 Suppl):S68–70.

-

Patulny R, Muir Thou, Powell A, Flaxman S, Oprea I. Are we reaching them however? Service access patterns amid attendees at the headspace youth mental health initiative. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2013;18(two):95–102.

-

O'Keeffe 50, O'Reilly A, O'Brien Grand, Buckley R, Illback R. Description and event evaluation of Jigsaw: an emergent Irish mental wellness early intervention programme for immature people. Ir J Psychol Med. 2015;32(i):71–7.

-

Birchwood 1000. Youth space and youth mental wellness. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;48:S7.

-

Laurens KR, Cullen AE. Toward earlier identification and preventative intervention in schizophrenia: bear witness from the London Child Health and Evolution Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(4):475–91.

-

Rickwood DJ, Telford NR, Mazzer KR, Parker AG, Tanti CJ, McGorry PD. The services provided to young people through the headspace centres across Australia. Med J Aust. 2015;202(10):533–6.

-

Hetrick SE, Bailey AP, Smith KE, Malla A, Mathias S, Singh SP, et al. Integrated (one-finish shop) youth health intendance: best available evidence and time to come directions. Med J Aust. 2017;207(10):S5–18.

-

Lasalvia A, Ruggeri M. Renaming schizophrenia: benefits, challenges and barriers. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28(3):251–3.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Mario Maj for his comments on a draft.

Funding

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

All authors co-wrote and edited the manuscript. MC provided leadership for decisions of content, framing, and style and led the creation of the Figures and Table. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed nether a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third political party cloth in this article are included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilize, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/one.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the information.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this commodity

Cite this article

Colizzi, M., Lasalvia, A. & Ruggeri, M. Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care?. Int J Ment Health Syst 14, 23 (2020). https://doi.org/x.1186/s13033-020-00356-ix

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00356-9

Keywords

- Youth mental health

- Promotion

- Prevention

- Early intervention

- Multidisciplinary intendance

- Trans-diagnostic model

mcnameefinfireer02.blogspot.com

Source: https://ijmhs.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13033-020-00356-9

0 Response to "Examples of Preventative Projects for Family of Depressed Patient"

Post a Comment